The Chinese writer Hsieh Ho, at the beginning of 500 AD, wrote a treatise entitled:

“Notes on the Classification of Ancient Paintings” in which he set out the principles of painting of his time in the form of six principles.

As time passed, its six rules were also used to judge the aesthetics of calligraphy and were later used in the judgment of all arts, i.e. these six rules formed the basis for aesthetic judgment of the artistic traditions of Chinese culture.

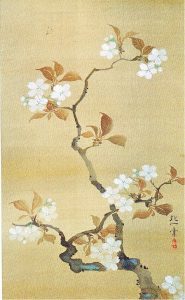

Imported in Japan during the Kamakura period (1185-1333) by Zen monks, the six rules were the basis of judgment for all traditional art forms (including ikebana).

The six rules are in descending order of importance, from the 1st (the one with the highest artistic value) to the 6th (the one beginners start with).

1st KI-IN-SEI-DO: state of mind, vital force, spiritual expression

The artist must sense the circulation of his own vital energy (Ki) and of the nature of the work, identifying himself with the work.

The concept of the artistic ideal is completely different from the Western one, since it states that if the work is not an expression of the spirit, it cannot be called a work of art.

2nd KOPPO-YOSHITZU: use of the brush “reduced to the bone”.

The artist must know how to capture the essential by highlighting the structural LINES, the bones, of the work, leaving out the unnecessary.

For the ikebanist it means thinning the plants, highlighting the lines and masses in a careful way.

The other four rules are mainly technical

3rd OHBUTSU-SHOKEI: give likeness in accordance with the object

The artist must draw the form in accordance with the nature of the work.

For the ikebanist it is the respect of the characteristics of the chosen plant, inserting it in the composition considering its natural growing position but also how this plant is represented in the Japanese imaginary and painting tradition.

4th ZUIRUI-FUSAI: use of color

The artist must apply colour in accordance with the nature of the work.

For the ikebanist it is the choice and color combination between the plants and between the plants and the container.

5th KEIEI-ICHI: spatial composition

The artist organizes the composition by placing the elements in the space available.

For the ikebanist it is the observance of the spaces of the Styles (which the Ohara school calls -kei, Kun reading of the kanji which is read kata in On reading) prescribed by the School and the balance between the masses and volumes of the various plants, the container, the place where the composition is set.

- DEN I-MOSHA: Transmission of the experience of the past by copying.

The beginner must start by copying the works of the masters trying to communicate the “essence of the brush” and the ways of the master, i.e. the copy must transmit the emotions and ideas of the master i.e. his Ki.

For the ikebanist it is the copying of the Styles (kata/kei) of the School.

Copying, in Western culture, is seen in a negative sense. For the ikebanist, copying the compositional schemes shown by teachers is important. This copying has several functions, both physical and psychological:

-it allows a gradual learning of the mastery of movements (use of scissors, anchoring techniques, modification and trimming of plants, etc.).-

The comparison with a model helps to diminish the expressive impetuosity of the pupil and, more generally, his presumptuousness.

-copying allows the pupil to incorporate the essential, the ‘vital breath’, the Ki of the original work.

In the Sung period (960-1279), still related to painting but applicable to all arts, the Six Canons were expressed by the:

SIX FUNDAMENTAL PRINCIPLES:

1 The action of the Ki and the energetic work of the brush go hand in hand.

For the ikebanist, the use of the scissors goes hand in hand with the action of Ki.

2 The basic design must be faithful to tradition.

The ikebanist must be faithful to the kata, to the styles of his school (for the Ohara school these are the Chokuritsu-kei, Keisha-kei, Kansui-kei and Kasui-kei ).

3 Originality must not despise Li, the principle or essence of things.

For the ikebanist it is to respect the nature of the plant and its natural growth habit.

4 Color, when used, must be an enriching factor.

For the ikebanist, the compositional structure is more important but it can be enhanced by the plant colour of carefully chosen.

5 The brush must be held with spontaneity.

The scissors must be held with spontaneity.

6 Learn from masters but avoid their mistakes.

In painting, Ki is given by the “movement of the brush”, hippo in Japanese, in the hands of the artist.

In the Japanese tradition, a work of art was defined as such when one was able to distinguish the presence of the artist’s Ki in his work (in the composition in the case of the ikebanist).

On the other hand, if we think of the expressive form of Ukiyo-e – woodcuts from the Edo period that represent popular, theatrical and legendary life – we see that when it first appeared it was not considered a work of art by the cultured Japanese class. The reason for this lack of consideration was precisely the lack of recognition of the presence of Ki in this art form.

The educated class of the time believed that the artistic sensitivity of the brushstroke was lost in the carving of the wood of the mould.

Even if the carving was perfect, they saw only the shadow of the artist’s sensitivity and skill in the use of the brush in the matrix; therefore a work without a clear identification of Ki could not be considered a work of art. In addition, the themes dealt with by Ukiyo-e were considered too popular and therefore failed to meet the requirements of elegance and refinement demanded by noble taste.

Not being appreciated as an artistic form, the Ukiyo-e woodcuts were used in the same way as we use old newspapers to package artefacts sent abroad: this fortuitous event led to the discovery of Ukiyo-e in the West.