see also Art. 17

Feng-shui (wind-water) – hōgaku (direction-angle)

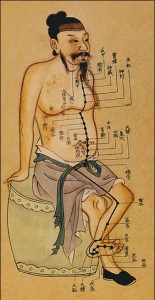

deals with the correct interaction of the human being with his natural environment and is the art of identifying and interpreting the action of Ki cosmic energies (electromagnetic, thermal and gravitational) that circulate in the human being and in his environment mainly through air (breath in man, wind in nature) and water (blood in man, rivers in nature).

In ancient China and Japan, nature was regarded as a living, breathing organism.

This kanji represents the vital energy that flows in the universe and enlivens every form of existence on the earth – including stones and rocks – and is written Ki (Hepburn transliteration system) or Ch`i (Wades-Giles system) or Qi (PinYin system).

See article 50 on the transliteration of the Japanese language.

Ki can be “good” or “bad”, stored, dispersed, channelled, and is responsible for all the changes in the universe and is expressed through the two principles Yin and Yang that control the universe, not arbitrarily or randomly but through unchangeable and humanly unfathomable laws.

This view of the universe may appear irrational and unscientific, but it has greatly influenced both Chinese and Japanese everyday life and culture.

For example, the vital force Ki has always been used to define an artist, since the Roppo (six cànons of HSIEH HO) places as the first and most important rule the fact that the artist expresses his Ki and that of his work. See article 7

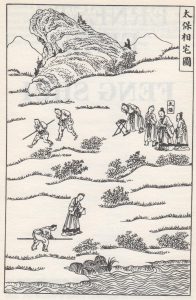

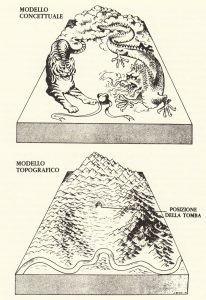

One of the purposes of feng-shui is to locate the ‘dragon lines’ that carry the earth’s energy, i.e. to identify the earth’s energy lines that are comparable to the meridians of the human body considered by acupuncture. This helped to capture the beneficial energy of the chosen location and to banish the malefic energy. Was used for example for indicating the correct location where and how to build a tomb, a house or a city.orretta posizione di una tomba o una casa o una città.

| Chinese feng-shui masters searching for dragon lines (4th figure from right consulting a compass on a small table) late Chìng period (late 19th century) |  |

The ancient capitals of Nara, Nagaoka and Heian-kyo – today’s Kyoto – were built according to the rules of Feng-Shui, as well as the Tokugawa castle around which today’s Tokyo was built, haphazardly and without following feng-shui.

Buildings such as the Imperial Palaces, the residences of the aristocracy and even all the elements that make up their gardens, from stones to paths to ponds to streams to waterfalls and trees, have been laid out according to these rules since ancient times.

The theory of Feng-Shui is very complex and is based on the Yang-Yin Theory, the 12 animals of the Chinese zodiac, the 5 elements (fire, wood, earth, water and metal) and the 64 hexagrams of the I-Ching.

The importance of Feng-Shui was such that, for example, it was thought that even if just one of the large stones in the garden was misplaced it would fail to protect the house from evil energies and this failure could cause illness or even the death of the owner.

Like everything produced by Japanese culture, ikebana has also developed in accordance with the rules of Feng-Shui, particularly those relating to the four protective Cardinal Deities and the avoidance of straight lines.

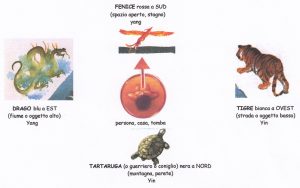

1- THE FOUR CARDINAL DEITIES

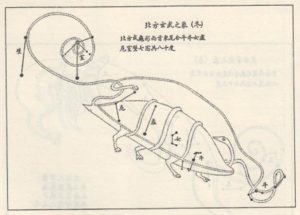

In ancient China, and consequently in ancient Japan, the stars of the firmament were grouped, according to the four seasons, into four major constellations: the tortoise, tiger, phoenix and dragon.

In the picture below the constellation of the Turtle with the Little Dipper and the Polar Star visible in the lower right-hand corner

The same animals, positioned in symbolic concordance (according to Tai-ji) with the orientations and colours, North black tortoise, West white tiger, South red phoenix and East blue dragon.

They have the task of “protecting” the person, the tomb, the house from evil forces.

Contrary to the West, which places the south at the bottom and the north at the top, in ancient times in the East the position of the two cardinal directions was reversed, so on maps and in Taoist symbolism the black turtle protecting the north is placed at the bottom and the red phoenix, protecting the south, at the top. (see article 15th )

Western concept Sino-Japanese concept

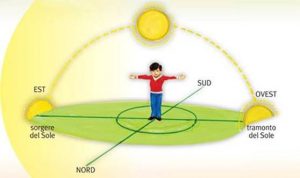

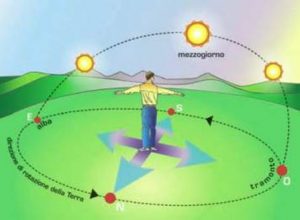

In China and Japan, south – corresponding to the sun – was considered the most important direction and therefore considered yang while north, its opposite and less important, was considered yin

For this reason in the ancient compasses used in the Far East, the magnetic needle (red tip in the picture) pointed south.

East is also considered yang because the sun, which is born in the east, rises in the firmament and radiates more heat. Rising and rising are yang characteristics. Its opposite west is believed to be yin, direction in which the sun decreases in heat and descends, decrease and descent are yin connotations.

In reality, the -person, house, tomb- must be facing south geographically surrounded by the four animal-symbols that protect it; both the type of animal and its position are consistent with Tai-ji.

There are two flying animals on the Yang/sky side (east and south) dragon and phoenix and two land animals on the Yin/earth side (north and west) tortoise and tiger.

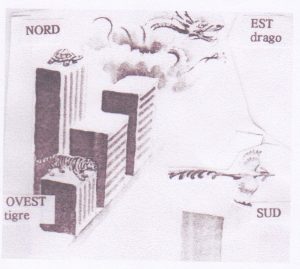

| Above is an example of the layout of a tomb protected to the north by the tortoise (high mountains), to the west by the tiger (hills), to the east by the dragon (medium height mountains) and to the south by the phoenix (empty space and water). |  |

|

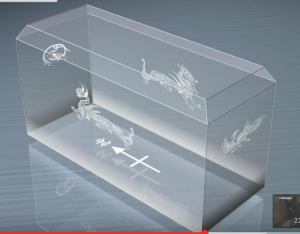

Sketch of a Chinese emperor’s sarcophagus with the four protective animals engraved on its walls.

|

|

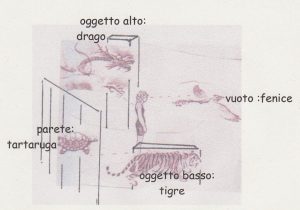

In order for a building to be in a protected situation, it must ‘look’ to the south and there must be an empty space in front of it (the Red Phoenix), behind it to the north is a very tall building (the Black Turtle), to its right side to the west is a low building (the White Tiger) and to its left side to the east is a slightly taller building (the Blue Dragon).

|

|

|

Applied to a person, this person, in order to be protected, must have a high object to his left (symbolized by the Dragon) and a low object to his right (symbolized by the Tiger) free space in front (Phoenix) and a wall behind (Tortoise).

|

|

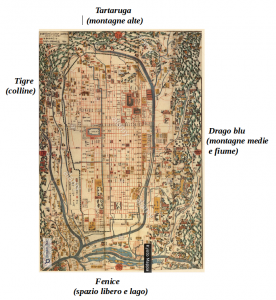

The ancient capitals Fujiwara (694-710), Nara (710-784), Nagaoka (unfinished and abandoned after 10 years) and Heian-kyo (794-1868) -the present Kyoto, map above- as well as the first shogunal capital of Kamakura (1192-1333) were built following the rules of Feng-Shui ( see Art. 17°) whereas present-day Tokyo was built haphazardly and without following the feng-shui rules.

|

|

|

Above is a map of ancient Edo (present-day Tokyo) with an apparently free space in the centre marked with the Tokugawa coat of arms (three leaves of Althea) where their residence stood, with the main daimyo dwellings – arranged on a north/south axis – to the south, one next to the other. All this is surrounded by the rest of the city, which has grown haphazardly because Edo was not born as a capital city.

|

|

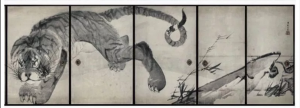

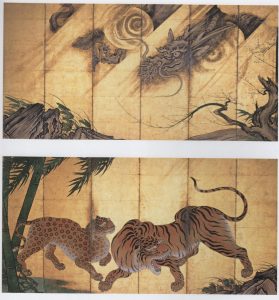

The two protective animals dragon and tiger were frequently painted on screens as can be seen in the painting below by Hasegawa Tōhaku (1539 – 1610)

|

|

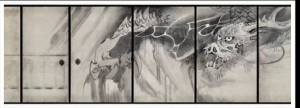

or in sliding doors like the ones by Nagasawa Rosetsu (1754–1799) below

Two six-panelled screens:

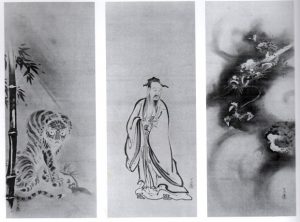

Triptych by Kano Tsunenobu (1636-1713):

In the Edo Period it was fashionable to give a triptych with a drawing of famous people in the center, on its left side -yang side- the dragon -yang animal- and on its right side -yin side- the tiger -yin animal- protecting it.

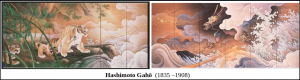

Screens by Eitoku Kanō ( 1543 – 1590)

Or screens with the dragon and the tiger.

Since drawings on paper, on screens and sliding doors are “read” from right to left, the yang/ most important dragon is placed first on our right and the tiger/ yin -less important- is placed second, on our left.

A leopard was painted next to the tiger: in Japan, as only the skins of these felines arrived from abroad, the leopard was believed to be the female of the tiger-male.

Consequently :Tiger-male/yang, most important, drawn first in the view from right to left, leopard (wrongly believed to be the female/yin of the tiger), drawn second:

In the double screen the dragon, being yang compared to the tiger, it is placed to the right of the screen with tiger and leopard, and is the first to be “read”.

Sliding doors by Kano Tan`yu 1630 circa

In this depiction of Buddha’s death, at the bottom right-hand corner, among all the pairs of animals that have come to pay their respects, you can see the tiger/leopard pair.

See the detail below:

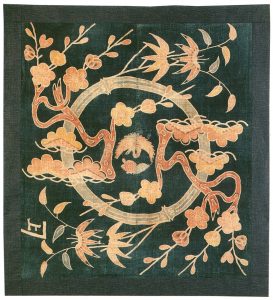

Above a Kimono of the late Edo-early Shōwa period with the two protective animals yang, phoenix and dragon

Furoshiki cloth, Meiji period, with two protective animals in the centre, from the south -phoenix- and from the north -turtle-.

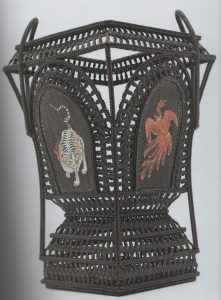

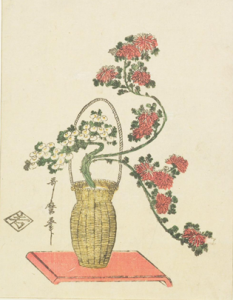

Hanakago: bamboo ikebana Basket dated 1926 with tiger and phoenix.

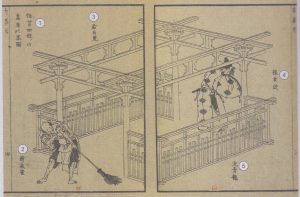

It is interesting to note that in this manga by Katsushika Hokusai (1760-1849) taken from the book -Hokusai, le vieux fou d’architecture-representing an ancient Torii (nowadays composed of a single arch but in the past composed of four) the inscriptions at numbers 2, 3, 4 and 5 indicate that it was spatially arranged in accordance with the four protective deities: 2 vermilion bird, 3 white tiger, 4 black tortoise, 5 blue dragon, with the main entrance facing south.

IKEBANA

When the rules of ikebana composition were created during the 15th century, the feng-shui scheme already in use in everyday life was taken as a reference, so the measurements and positions of the plants were designed to be in accordance with its symbolism and in harmony with the positions of the four cardinal deities:

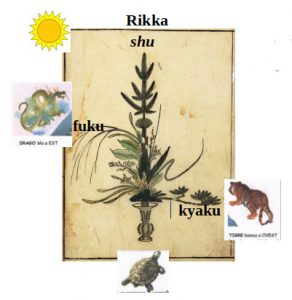

In the Rikka the main element (Shu for the Ohara school) corresponds to the person – house – tomb to be protected and is protected by the Fuku in the position of the Dragon on the east side and by a Kyaku in the position of the Tiger on the west side.

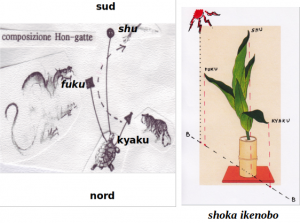

The composition is seen “from behind”, that is from the north (position of the Turtle), as it is customary in Ikenobo rikka and shoka (concept that will be explained in the following paragraphs).

At the beginning, when the first compositional rules of ikebana were formed, the Rikka was always in the style that the Ohara school calls “Vertical” i.e. with the Shu in the centre and vertical: the composition, “looking” to the south (the sun at its apex is ideally placed on the side of the yang culmination between the Dragon and the Phoenix ) and seen from the north (Turtle), is congruent with the rules of Feng-Shui: shu is protected on its left side by a relatively high fuku (Dragon) and on its right side by a relatively low kyaku (Tiger).

In the Edo period new types of ikebana appeared (see Art 15) deriving from a simplification of the Rikka and called shōka in the school Ikenobo and seika in the other schools: only three main elements are used but the respect of the laws of feng shui has remained unchanged, maintaining the protective scheme of shu with a fuku/Dragon high in the east and a kyaku/Tiger low in the west.

Also in the shōka, the sun is located at the point-maximum yang in the drawing.

From Rikka and shōka, that was the only structured style from the birth of ikebana until the first part of the Edo period, the Oblique and Cascade styles derive; in these styles the shu has changed position and the reference to the 4 Protectors no longer exists.

Shu è “protetto” da fuku/drago e da kyaku/tigre

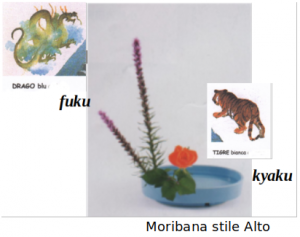

The styles of the Ohara school derive from seika and the only style in which the influence of feng shui is still perceptible is the Alto style while it is no longer perceptible in the other styles as the position of shu and fuku have changed.

The rules about positions and heights in ikebana are also coherent with the four cardinal deities where shu (circle) corresponds to the person to be protected, fuku (square) corresponds to the dragon and kyaku (triangle) corresponds to the tiger.

The composition is seen ‘from behind’, i.e. from the north (position of the turtle), as is customary in Ikenobo rikka and shoka (a concept that will be explained in the next articles).

AVOID STRAIGHT LINES

Feng-Shui views straight lines negatively because they facilitate evil energy to flow, while it prefers curved lines because they deflect such forces.

For example, roads, streams, canals, rivers flowing in a straight line bring evil influences; on the contrary, roads and waters with winding and curved lines are an indication of the presence of beneficial forces. In general, any shape with straight lines, angles and edges is considered virtually dangerous.

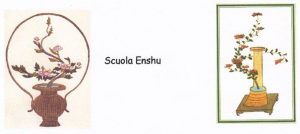

Even in ikebana (with the exception of the early Rikka with the straight Shu) all the Schools of the past have always used curved lines, arriving, only in the Edo period, at excesses such as the example of the Seika of the Enshu School that used curves that may appear to our eyes “extreme, exaggerated, unnatural, baroque, artificial”, with S-shaped bends, very accentuated and complex.

Bearing in mind this dislike of straight lines in Feng-Shui, even the ikebanist of the Ohara School must avoid them, apart from specific rare exceptions.

Plants in their natural state in Japan appear more “suffered” because the forces of nature are much more powerful than in Europe and therefore “leave their mark” on the plants; as European plants are less “marked” by nature than Japanese ones, they must be moulded by the ikebanist. This is even more evident when using plants grown in greenhouses or nurseries or other protected places which, unlike plants grown in nature, do not show (with their straight lines) the effects of the forces of nature (wind, rain, sun, cold, snow, drought). They must therefore be “manipulated” by the ikebanist in order to remove the rigidity of the lines to make them more natural and less artificial.

The “amount” of manipulation will be less on a “young” element and more on an “old” element because the “young”, in theory, has been exposed to the elements for less time than the “old”.