For the religions and philosophies that have influenced the history of ikebana the importance given to the EMPTINESS is great so we find it in ikebana compositions expressed at various levels.

In Western culture emptiness has a negative value, of deficiency (empty mind, empty stomach, empty life, sense of emptiness) but in Japan and China it has a positive value and to understand this value it can be useful to shift the attention from the concept of emptiness, which can leave us uncomfortable, to the one we are more familiar with of SILENCE (i.e. emptiness of sounds), which for us evokes a feeling of peace, quiet, serenity, without noise or disturbances:

The call of a bird,

the quietness of the mountain becomes deeper;

the rumble of an axe,

the peace and quiet of the mountain grows

Chinese Zen poetry by anonimous

We find the EMPTINESS in ikebana :

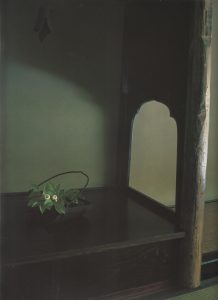

1 AROUND THE COMPOSITION

|

That was traditionally placed on the Tokonoma, empty by definition, or nowadays in a place in the house with a void around it, i.e. free from any object that might distract attention from the composition itself. |

|

|

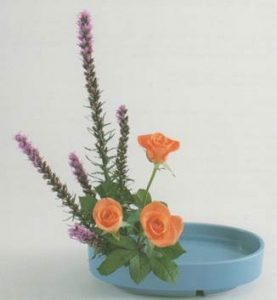

2 AROUND THE INDIVIDUAL PLANT ELEMENTS

|

(C) Ohara School of Ikebana |

|

3 AROUND THE INDIVIDUAL PLANT ELEMENTS

That not only allows to see the individual components but also enhances concepts, so important for Buddhism, such as asymmetry, harmony and rhythm. For Buddhism each element of the composition does not have its own consistency and meaning, but only acquires them in relation to the other elements.

The relations existing between the measures of plants, both among them and in relation to the measures of the vase, highlight the inter-dependence: for Buddhism no being or phenomena exists on its own, but only in relation to other beings or phenomena: everything in the world is revealed in response to certain causes and conditions.

Even in the no longer used system of calling Heaven-Man-Earth the three main elements of the composition in Shoka and Seika highlighted these relationships.

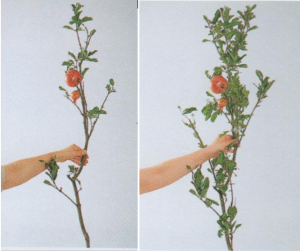

4 IN THE PLANTS THEMSELVES

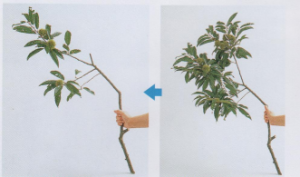

example with a maple branch

Remove the redundant material, starting from the side branches to the surplus leaves and flowers. In branches leave an irregular alternation between empty spaces (remove all the leaves) and filled spaces; the latter must have different volumes.

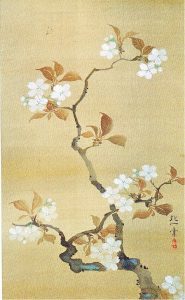

The method of removing the superfluous in Ikebana is inspired by the method used in paintings: in this detail of Eikyu Matsuoka’s (1881-1938) painting entitled “Ladies of the Court in spring dresses” both the pine branches and the flowering ones are painted not as they appear in nature. Here we can see that the pine has only the new apical tufts without the old needles and the flowering ones have been painted like they were ideally “thinned” like we do in ikebana so that both the branch and every single cluster and every single flower are clearly visible

or as in this example of Ogata Korin, in which the azalea is not painted as thick as in nature but idealised by painting only the essential, without the superfluous, and maintaining an optimal balance of “forces” between branches/yang and flower-leaf/yin.

Another example with branches

|

|

scuola Ohara |

|

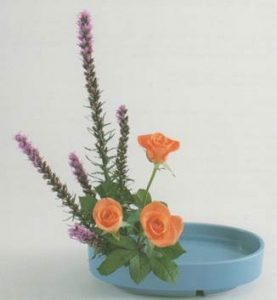

5 THE EMPTYNESS AT THE MOUTH OF THE VASE

![]() scuola Ohara

scuola Ohara

In the Ohara School the empty space at the mouth of the vase, although not visible because it is covered by vegetables, has been preserved in the tall vases in which the vegetables emerge only from ¼ of the mouth leaving the other ¾ empty and is evident in the lower vases, although the surface area varies according to the seasons, to the styles and to the type of plant used.

In brief, the EMPTYNESS around plants highlights both the characteristics of the single plants and the mutual relationships that are important for Buddhism.

As G. Pasqualotto writes in the Aesthetics of Emptiness:

Reducing the quantity of the elements increases the possibility and the intensity of perceiving their value, i.e. EMPTY produces quantitative deprivation to produce qualitative wealth.

.

The minimization of the elements corresponds to a maximized expansion of their qualities and, consequently, the conditions for a maximum of perceptual intensity are produced.

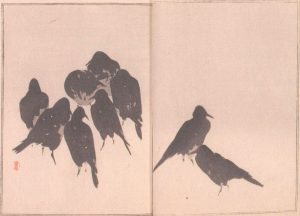

Examples of emptiness in drawings

Watanabe Seitei (1851-1918)

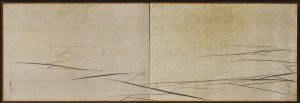

Two screens by Maruyama Ōkyo (1733 – 1795)

Ice with cracks, 1780

Ice with cracks, 1780

Ducks on the beach

Ducks on the beach