For Zen Buddhism, any human activity, especially manual activity, can be used as a “path”, a Way that leads to “awakening”/satori or enlightenment.

The purpose of the specific activity chosen as the Way is not the goal but the “process” that leads to it.

This means doing something not for the result but to commit ourselves because doing the specific acts of that activity helps to change ourselves in the ways indicated by Buddhism in general and Zen in particular.

If any manual activity can potentially be used as a medium to pursue this Way, even more

a discipline (artistic or ‘sporting’) can be used for this purpose.

Since the time of the first shogunate of Kamakura (1185-1333) a group of traditional arts have been influenced by Zen Buddhism and, in the Edo period, used by seculars as a Way ( Dō ) to enlightenment; these disciplines are recognizable by the suffix -dō (= Tao = way):

Martial arts:

Kyu-dō (way of the bow), Ken-dō (way of the sword), Karate-dō (way of the bare hand),

Ju-dō (way of yielding), Iai-dō (way of drawing the sword)

Performing arts:

Cha-dō (tea ceremony), Sho-dō (way of writing), Ka-dō (way of flowers or ikebana), Kō-dō (the way of scents)

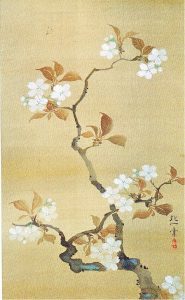

Other artistic expressions, even if they do not have the suffix -dō, have also been influenced by Zen, such as: Nō theatre, Bonsai, Suiseki (stone collection), traditional Japanese architecture, Kaiseki cuisine, Kare sansui (“dry” gardens ), Raku pottery, Haiku poetry, Suiboku-ga (diluted ink painting).

How can the manual execution of an Ikebana be used as Ka-dō, that is, as a character-forming discipline, as a way of personal fulfilment, as a way of liberation?

To explain this to those who do not know Zen Buddhism, one can say that this is possible because the rules of ikebana composition are a “manual application” of the ideas that Zen promotes. By applying these rules consciously and repetitively while composing, they are assimilated and made their own by the ikebanist and become his or her ethical characteristics.

For example, the repetition of the manual exercise of “removing the unnecessary leaving only the essential of the branch” (for Zen, the concept “less is more” applies), if done with consciousness, is transformed into a spiritual exercise whereby one learns to “remove the superfluous leaving only the essential” also in other situations in one’s life.

The “making a space around the composition, around the plants and in the plants themselves”, leaving only what is necessary (always the concept of “less is more”), trains the ikebanist to “make a space” in his mind, that is, to let thoughts pass through, without being influenced, considering them only thoughts and nothing more.

The practice of considering relationships of “strength”, of measures, of volumes, by constructing an ikebana exercises the conscious ikebanist to give greater value to the relationships with people, animals, nature, objects, the environment, etc.

Attempting to create an Ikebana that is ‘shibui’ (austere, elegant, sober, refined, quiet) and ‘wabi-sabi’ ( refusing the ostentation, poverty as voluntary relinquishment), two qualities favored by Zen, exercises the ikebanist in ‘shibui’ and ‘wabi-sabi’ behaviour in everyday life. Pursuing this form of ikebana leads to actions that are poor in appearance but rich in meaning, simple but important, sober but effective, and this means that a formal refinement in the material execution of the composition (practicing the art of ikebana ) leads the ikebanist to an ethical improvement.

A poem by Constantinos KAVAFIS (1863-1933) expresses very well the Zen concept that ‘the goal is the path we take’. :

Ithaka

As you set out for Ithaka

hope the voyage is a long one,

full of adventure, full of discovery.

Laistrygonians and Cyclops,

angry Poseidon- don’t be afraid of them:

you’ll never find things like that on your way

as long as you keep your thoughts raised high,

as long as a rare excitement

stirs your spirit and your body.

Laistrygonians and Cyclops,

wild Poseidon- you won’t encounter them

unless you bring them along inside your soul,

unless your soul sets them up in front of you.

May there be many a summer morning when,

with what pleasure, what joy,

you come into harbors seen for the first time;

may you stop at Phoenician trading stations

to buy fine things,

mother of pearl and coral, amber and ebony,

the sensual perfume of every kind-

as many sensual perfumes as you can;

and may you visit many Egyptian cities

to gather stores of knowledge from their scholars.

Keep Ithaka always in your mind.

Arriving there is what you are destined for.

But do not hurry the journey at all.

Better if it lasts for years,

so you are old by the time you reach the island,

wealthy with all you have gained on the way,

not expecting Ithaka to make you rich.

Ithaka gave you the marvelous journey.

Without her, you would not have set out.

She has nothing left to give you now.

And if you find her poor, Ithaka won’t have fooled you.

Wise as you will have become, so full of experience,

you will have understood by then what these Ithakas mean.

Translated by Edmund Keeley/ Phillip Sherrard

The poem is from www.cavafy.com

The birth of Zen, in tradition, is linked to a flower:

Buddha was once asked to give a sermon; he picked a flower (of a fig, according to Dōgen, as written in the Shōbōgenzō, but usually it is a lotus) and, in silence, slowly with his arm outstretched, showed it to his followers. Only one, the wisest (Mahakasyapa = Kasiyapa the great) sensed the “silent” message of the Master and smiled with understanding: thus was born the silent teaching of Zen. Mahakasyapa was the first of a series of patriarchs who brought Zen from India to Japan, where the shogunal nobility, already in the Kamakura period, preferred it to the other Buddhist currents practiced by the imperial nobility, because it was more in keeping with the warrior mentality.

Zen gave Ikebana the same characteristics given to the ideal lifestyle of the shogunale nobility. These characteristics were applied in all manifestations of daily life: from the way of building houses, to martial arts and other arts such as the tea ceremony, Nō theatre, calligraphy, Haiku poetry, dry gardens, Kaiseki cooking, Raku pottery and more.

These characteristics can be summarised in the following concepts, expressed by the Zen monk Shin’ichi Hisamatsu in his book “ZEN and the fine ARTS”:

General characteristics that apply to all arts Specific characteristics for ikebana

Simplicity In the choice of the vase and materials

All the redundant parts of the vegetals

Austerity are removed, leaving only the essential parts

Asymmetry In numbers, positions and inclinations

Avoiding any signs of artificiality:

Naturalness the composition must give the idea that

human did not intervene

The composition must radiate a sense

Subtle depth strength and a remarkable power of suggestion

(Yugen) that suggests some hidden quality

Peace of mind The composition must suggest a sense

of deep calm